Supporting a colleague who has made a mistake

In a recent blog, we featured a discussion between Catherine Oxtoby, Head of Underwriting and Pricing at the Veterinary Defence Society (VDS), and PhD Researcher at the University of Nottingham, Julie Gibson about mistakes in veterinary practice; how to learn from them and prevent them from happening again. They also spoke about the emotional repercussions of making a mistake. In this blog, we consider how one might offer support to a colleague who might be struggling to come to terms with the emotional and the (perceived) reputational repercussions of making a mistake. When we worry about mistakes, it affects how we work. Too often we consider mistakes we make as signs of our own ineptitude. So, to spare ourselves the anxiety and frustration, we often don’t constructively reflect on the mistakes we’ve made. We push forward, we try our best to learn from them, we shut down if anyone asks us about them. And that’s the catch-22. Because not reflecting on your mistakes is the biggest mistake you can make. It leads to the internalisation of feelings of disappointment and distress, perceptions of failure, anxiety and (potentially) thoughts of leaving the profession. Efforts to ensure that colleagues feel supported, and that organisations learn from their mistakes, centre on communication. Crucially, on a supportive forum for disclosure. Whether they succeed or fail will depend in large part on the culture of the practice: the entrenched beliefs and attitudes of the team, the structures that provide platforms for conversations and behaviours, the history, stories and experiences that colleagues remember. Organisations with embedded communication structures and an open culture foster trust, shared goals and teamwork. Recognising the importance of facilitating communication is the first step. The next is to prioritise it as the platform for growth and improvement, which can be tricky in the midst of incessant competing demands. Mistakes happen. We know it's uncomfortable, it's a real thing and it's a real problem for people. We know it really upsets clinicians and that it can have an impact on the care they deliver. It can also have an impact on their joy in work, on their experience of work and whether they want to go back to it and at what level when, and if, they do go back. It's a lovely thing, in some ways, as it demonstrates how much they care about their patients, their clients, their standard of work and their performance. But when things go wrong, it can be a really uncomfortable, painful place to be. So how might we support a colleague who has made a mistake? We really want to help, yet we don’t quite have the words or the tactics. You might have felt yourself freeze in these moments, paralysed by the thought that anything you say or do could be a little awkward, or even make things worse. It’s difficult to know what works best to help friends and colleagues effectively when something has gone wrong in practice. Moreover, the support we do provide, such as giving advice, is often ineffective. Part of the challenge is that there are just so many possible ways to intervene. A survey of the methods that people used to manage their friends’ emotions identified 378 distinct strategies1, including allowing the other person to vent their emotions, acting silly to make the other person laugh, and helping to rationalise the other person’s decisions. Given the huge variety of strategies, it’s no wonder that deciding what to do can be a little overwhelming. The good news is that the skills you’ll need to support a colleague can be learnt. In the remainder of this blog, we will consider five strategies to help you provide more effective emotional support to those who are struggling.Why it’s important to reflect

Communication is the bedrock of a supportive team culture

How to support a struggling colleague

Being supportive isn’t easy

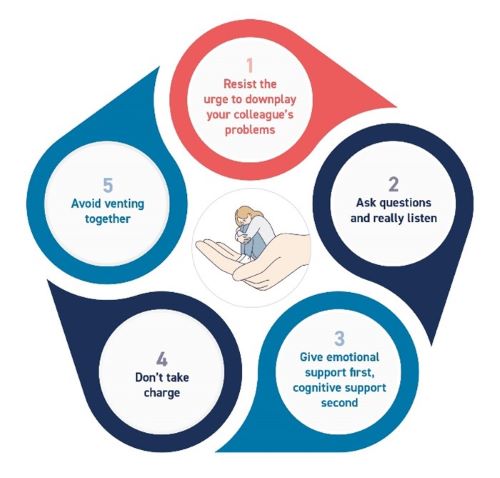

But being supportive is a skill that can be learned

1. Resist the urge to downplay your colleague’s problems When we think that someone is catastrophising something that (to us) is not a big deal, it can be tempting to ignore them, downplay them or be dismissive, but that would be a mistake and will likely end badly. Whatever your own take on your colleague’s dilemma, it’s important to be responsive to their feelings, and to prioritise trying to understand how they feel. So, you might share a thoughtful message, showing that you’re trying to understand how your colleague feels: ‘I get why you’re upset. I know you’re a hardworking and smart person’. In the longer term, a good way to work on being more responsive and less dismissive is through setting compassionate goals. These involve focusing on supporting others, being constructive in interactions, and being understanding of others’ weaknesses. 2. Ask questions and really listen Just as playing down a colleague’s problem is unwise, so too is trying to empathise too quickly, including jumping in with rapid advice. While this impulse is understandable and quite normal, it is also likely to go wrong. Although we tend to assume that we can tell how other people are thinking using our empathy, research has shown that we’re actually really bad at taking other people’s perspectives. One study, led by Tal Eyal at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev2, involved researchers asking people to put themselves in another’s shoes in 25 different contexts, including taking other people’s perspectives on movies, on activities, on social issues, and even on whether jokes were funny. In all these experiments, trying to take another person’s perspective didn’t work, and sometimes it even backfired. So how might you best address the situation instead? In the research by Eyal and her colleagues, directly asking was the only thing that helped one person understand how another person felt. This suggests that it would be better to slow down and start by asking directly how your colleague is feeling, rather than thinking about how you might feel in a similar situation. In short, we’re not as good as we think at intuiting other people’s feelings, and it is better to ask questions and listen to the answers. Listening well can also be a challenge, but again there is psychology research that can help. To be a more effective listener, you can begin with two easy tactics. First, be attentive to the other person, and signal that you’re listening carefully by using nonverbal signals (such as nodding and smiling) and brief phrases (such as ‘Mmhmm’ or ‘Oh really?’). Second, provide ‘scaffolding’ questions that help your colleague to elaborate on their story or their feelings, such as: ‘And what happened next?’ or ‘How did you feel after that?’ This can help them feel supported and heard. These skills may seem self-evident, but they’re particularly easy to forget in the moment, as we get distracted by our phones, or inclined to hurry our colleague along to get to the point of their stories. A related technique to try is active listening, which is commonly used by therapists, and relatively simple to implement. One form of active listening involves paraphrasing what your colleague is saying in your own words, which can help them feel better 3. Give emotional support first, cognitive support second In contrast to downplaying a colleague’s problem – helping them see a situation in a positive light (known as reframing) is a supportive strategy. Jumping straight to discussing the bright side might leave your colleague feeling as if you aren’t getting it. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to find a silver lining at all – but, rather than beginning there, better to validate and comfort your colleague as he talks through the situation. Once you’ve shown that you get how he feels, then you can help him find the bright side, which is a form of cognitive support in the sense that you’re helping your colleague to think differently. It’s important to provide both emotional and cognitive support because, although people prefer to receive and provide emotional support (and to avoid cognitive support), emotional support alone is often ineffective at making people feel better over the long term. Using emotional support first and cognitive support second makes people feel better, reaping the benefits of both approaches. One additional concern with cognitive support is making sure that the reframe you suggest doesn’t slip into invalidating or downplaying your colleague’s feelings. The dividing line here can be difficult to navigate. The key is to ensure your reframe doesn’t negate your colleague’s feelings that the initial situation was upsetting. Instead, focus your reframing on unexpected upsides not yet considered, or future avenues to move past the initial problem. 4. Don’t take charge Although you have the best intentions, telling your colleague straight up where they went wrong, and how to avoid the situation recurring, would be a mistake. Very direct and obvious help can sometimes make people feel as if they are helpless. Resources such as the VDS's VetSafe platform could help here. In the aftermath of a mistake, VetSafe offers ‘cognitive support’ through root cause analysis of the situation - a method of problem solving that aims to identify the root causes of problems or incidents based on the principle that problems can best be solved by correcting their root causes as opposed to other methods that focus on addressing the symptoms of problems or treating the symptoms. 5. Avoid venting together Sympathising with a colleague’s dilemma and venting together might seem like a supportive strategy that shows you’re both in the same boat and you’re happy to talk it over at length. However, this approach can go too far and can sometimes pull you and your colleague into a downward spiral of negativity. Although talking about problems can help, if taken to an extreme, it can become a problematic issue called co-rumination. This involves talking excessively with other people about problems, and constantly dwelling on those problems together without looking for solutions. Such behaviour results in both people feeling worse, with co-ruminating associated with increases in anxiety and depression over time. How might you stop that downward spiral? The good news is that simply knowing that co-rumination exists will likely help you avoid these kinds of negative spirals. So, begin by being on the lookout. If you identify the venting spiral, distraction can interrupt that feeling of being stuck in a problem. Go do something else that distracts you both, before coming back to figure out how to deal with the issue. At this point, you might consider enacting the validate-and-reframe strategy outlined above. Reframing can interrupt spirals of rumination. VDS members can find support in many ways from the VDS on the themes raised in this blog. Developed by the VDS, VetSafe is the Society’s confidential adverse event reporting tool. It's online and available as an app too. Along with the VetSafe tool itself, you’ll find resources, processes and frameworks that will support those conversations. For more information go to: www.thevds.co.uk/aboutvetsafe In addition, VDS Training provides a range of non-clinical training for which VDS members receive an exclusive discount. Some of the training provided covers themes raised in this blog around imposter syndrome, confidence, communications and online complaints handling. For more information go to www.vds-training.co.uk. Note 1: Niven, K., Totterdell, P., & Holman, D. (2009). A classification of controlled interpersonal affect regulation strategies. Emotion, 9(4), 498–509 Note 2: Eyal T, Steffel M, Epley N. Perspective mistaking: Accurately understanding the mind of another requires getting perspective, not taking perspective. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2018 Apr;114(4):547-571. doi: 10.1037/pspa0000115. PMID: 29620401.Key points – How to support a colleague who’s struggling to come to terms with a mistake:

Extra help from the VDS